This work was created on Cameraygal and Wangal Country. In acknowledging the traditional owners of this Country I would like to pay my respects to Elders past, present and emerging, and to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Denise Corrigan spoke to David Watson about In the Woods in May 2022…

What was the inspiration for this work?

In the Woods evolved during last year’s lock down, at a time of reading, routine and unaccustomed confinement. Each morning before breakfast I’d immerse myself in a few pages of (Australian author) Eleanor Dark’s remarkable and today-somewhat-neglected trilogy of historical novels re the fledgling, often floundering Sydney colony (e.g. The Timeless Land, Storm of Time), before taking off to the local park for a few laps of the oval and its adjoining bush track. Afternoon walks would sometimes take me farther afield, pushing to the furthest radii of our 5 km ‘bubble’.

‘Our’ bubble: as COVID cases and hospital admissions rose across Sydney in September 2021 health orders decreed that residents limit travel to within 5 km of their homes.

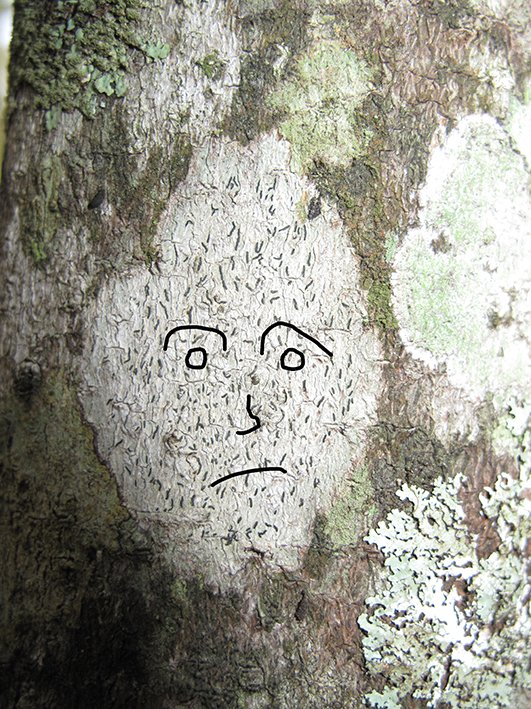

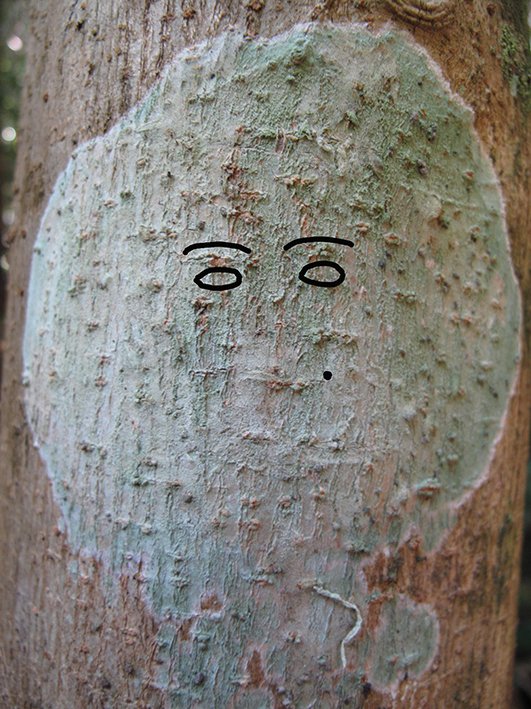

On the lower north shore I came across several beguiling slivers of harbourside green – council reserves I’d never before visited – with towering eucalypts and pretty streams. Here dotted amongst the bush beside well-maintained walking tracks the lives of Sydney’s colonists and early settlers were celebrated upon municipal plaques. Having – to my great shame – only in the last decade learnt some of the clan names of the first peoples (e.g. Cameraygal, Wallumedegal) of these attractive and today-affluent climes (e.g. Lane Cove, Longueville, Gore Hill, Greenwich) I began looking with my trusty G10 for visual clues which might signal absence and/or unease amidst the seemingly healthy stands of pittosporum, dogwood and lemon-scented gum, the fungi and the lichen, the obliging residents, their smiling children and straining canines.

Eleanor Dark describes the massing early colony as a ‘flood’[1] which inexorably (via disease, disdain, theft, dispersal, reprisal, murder) swept most of the harbour’s original inhabitants from their lands, and made way for ‘generations of greedy, undiscerning men’.[2] Contemporary writer Kate Grenville amplifies these sentiments: ‘the prison settlement of Sydney was a miserable place full of violence, grief and ugliness’ … the ‘partial, simplified or false story about settlement and pioneers that the colonists have been telling each other for 200 years has, until recently, obliterated the one about invasion and dispossession. How to look behind the story that dominates, to see the one that’s been hidden?’[3]

David Watson with In the Woods in Chamber 24 @ The Coal Loader in Waverton, May 2022

The first thing one notices about In the Woods are the six caricatures looking out at us from the ‘bush setting’ you have created within the coal loader chamber. Although a caricature is generally intended to satirise or ridicule, I find myself fondly drawn to some of your characters. Was this deliberate?

My challenge, it had become evident, was how to image an attempted obliteration which began decades before the medium of photography itself was invented. I wanted my portraits, my colonial ‘lichen-nesses’ to exhude a mix of blundering arrogance and inquisitive naïvete – so it was important that they be realised in a rudimentary, cack-handed manner. Fortunately I knew just the man!

So the reason, I suspect, that you as a non-indigenous person might feel somewhat fond of a few of my characters (as do I) is that terrifyingly (!) ‘they are us’ … still ‘settling’ and making home, still somewhat emotionally and spiritually bewildered by this new, ancient place. Still contrition-free.

Eleanor Dark writes of the early settlers being ‘affronted by a land which could … withdraw from them – leave them awkward and ignored, like uninvited guests. They wanted to rouse it, to mark it, to shatter its siesta with their commotions; to scar its earth with plough and fire, and raze its trees; to come and go, full of schemes and projects for its subjection; to build and traffic with what they could tear from it…’.[4]

Seems to me that we entitled, extractivist, fossil-fuelled white folk haven’t come very far in the intervening years. There is much to do, much to learn by listening intently to first nations’ peoples. There remain centuries of bastardry, dispossession and prejudice to address.

Independent writer-director James Vaughan cleverly explores some of this complex contemporary terrain (via a Sydney harbourside lens) in his nuanced 2021 feature film Friends and Strangers.

Why the lichens?

The lichens attracted me initially because of their often-white, face-like forms. By looking closely at examples great and small I found that I was able to isolate them ‘anthropomorphically’ in the frame upon their mottled bark surrounds. I was later to learn that the slow and symbiotic nature of lichen growth can depend upon connectedness [between host and ‘parasite’/‘epiphyte’] over hundreds of years, ‘a kind of antithesis of the survival of the fittest.’[5] Symbiotic interactions apparently fall along a continuum between conflict and co-operation. The consideration of ‘alien invaders vs collaborators & co-dependents’ usefully underpins both this work and my broader practice.

Interestingly, having decided to mount my portraits on locally-sourced eucalyptus boughs, I read that lichen customarily eschews eucalypts (especially those which shed their bark).

I know that you’d conceived and developed the imagery for In the Woods before you were offered space for the work’s display at The Coal Loader. Did the formidable presence/character of the chamber – with its 30 large blocks of sandstone jutting out at odd angles to form a high, concrete-ceilinged wall – present challenges/opportunities?

Yes indeed. Rarely have I had to work in such a site-specific manner. Having proposed initially to exhibit my images (on slender saplings) in a kind of defeated pile on the gravel, I found that the chamber’s floor area was insufficient (OH&S etc) for what I’d envisaged. With damp another potential issue (for works on paper), I decided to mount my digital prints more sturdily onto tin sheet (waterproof at least from the back) then attach them to eucalyptus boughs, which might lean upon and/or be secured to the chamber’s massive sandstone ‘cliff’. This configuration enabled my colonial characters to simultaneously rest upon and be subsumed/overwhelmed by the chamber’s massive industrial – yet still naturally patinaed and ancient – harbourside setting.

[1] Eleanor Dark, Storm of Time (Collins, London-Sydney, 1948), 341.

[2] Dark, 544.

[3] Kate Grenville, ‘I hijacked Elizabeth Macarthur’s story…’, The Guardian, 12 April 2022.

[4] Dark, 294.

[5] Robin Powell, ‘Lichen, the poster child of symbiosis’, Sydney Morning Herald, 17 April 2018.

David Watson speaks about In the Woods @ The Coal Loader in Waverton on 28 May 2022, as part of the environmentally-inflected biennial North Sydney Art Prize [video Janette Willett].

In the Woods

Below well-appointed homes on municipal walking trails beside nitrogen-enriched creeks, beyond interpretative signage and muddied archival photographs on aluminium, among fungi in remnant bushland upon rocky coves (where in 1789 aboriginal people lay dying of imported disease), the mottled visages of early colonists - those who stole, granted or were granted land, those who laboured, languished and sometimes prospered - appeared.

Gore Greenwich Willoughby Waverton Duckworth Prentice

Six pigment prints on cotton rag art paper 92 x 69 cm Edition of eight $500 each

In the Woods was installed @ The Coal Loader in Waverton as part of the North Sydney Art Prize, 14-29 May 2022. For this site-specific outing (see pic below) the work’s pigment prints were mounted onto .55 mm tin and attached to eucalyptus boughs.This iteration is available for purchase @ $5000.

The Coal Loader has an interesting history. From the 1920s to the 1990s it operated as an industrial depot transferring coal from bulk carriers to smaller coal-fired vessels. Some coal was also distributed to the local market by road. Today the site is a centre for sustainability run by North Sydney Council.

See also… Stephen Gapps, The Sydney Wars: Conflict in the early colony 1788-1817 (Sydney: NewSouth Publishing, 2018) ‘Devil devil’: The sickness that changed Australia, ABC News June 2021. Unsettled, Australian Museum August 2021

The interview (left) references and quotes from two of Eleanor Dark’s finest works of historical fiction,The Timeless Land (1941) and Storm of Time (1948). Meticulously researched and brought to life by deft interior rumination, the volumes memorably evoke the travails of life in the early settlement of Sydney and its environs, from 1788-1808.

Eleanor Dark (1901-85) was born in Sydney’s inner west (Croydon) and lived for much of her life in Katoomba, where eight of her ten novels were written. Her family home is today Varuna, The National Writers’ House.